Foot Position and Leg Training Article

Advanced Training Breaking Research & Overall Fitness

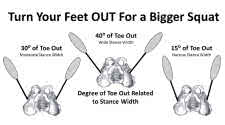

Many trainers say that you can selectively affect different areas of the leg by varying your foot position during leg exercises, such as squats and leg extensions. For example, to focus on the vastus lateralis muscle, or outer thigh, they advise you to point your toes inward, and to

target the vastus medialis. the teardrop muscle just above the knee, they suggest pointing your feet outward.

Researchers from the Human Performance Lab at the University of Miami in Florida decided to see if varied foot positions really do hit different thigh areas. They recruited 10 men who performed both squats and leg extensions during the experiment. The subjects used three foot

positions: toes out, toes forward and toes in. To test which areas of the thigh were affected by the different foot positions, the men also wore electrodes attached to an electro myograph machine which measures electrical activity in muscles. The results showed no difference in the

three foot positions during squats; in other words, changing foot position while squatting does not target specific thigh areas.

On leg extensions, however, the results were different. Performing leg extensions with toes pointed out did elicit more muscle activity in the quadriceps than the other two positions.

Growth Hormone Release During Exercise

Studies show that it takes a high level of exercise intensity to promote increased growth hormone release during exercise. Intensity in weight training refers specifically to load, or how much weight you lift. Heavier weights lead to quicker oxygen depletion in muscle, which leads to an increased lactic acid buildup. The increased muscle acidity is the signal that turns on the GH release. What happens when you train with moderate intensity, as the majority of people who lift weights do? Does that foster any type of increased growth hormone release?Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh recruited eight male subjects who performed two workouts of varying intensity levels. During the first workout they used weights amounting to 50 percent of their maximums, a moderate level of intensity. For the second workout they used weights averaging 70 percent of maximum. The results showed 3 that lactic acid increased more during the high-intensity workout, but growth hormone release was the same for both sessions. Therefore, the researchers found no significant correlation between increased muscle acidity and increased release during moderate-intensity exercise.

Hormones and Aging: Preserved by Exercise?

Most of the body's systems work on a use-or-lose-it principle. Past evidence shows that the endocrine or hormonal, system is no exception to this rule. For example, testosterone inmates peaks at age 19, that remains steady until about age 50 when it gradually starts to decline. This is reflected in a decreased sex drive, among other symptom Some evidence shows, however, if you continue to lift weights, yet can maintain a more stable hormonal profile, preventing the picipitous drop expected with age.Scientists from Pennsylvania State University Appalachian St University in North Carolina and the United States Olympic Training Center recently tested the hormonal responses to exercise of a 51-year-old former champion weightlifter. This subject was still competing successfully in Master's weightlifting events and was a two-time Olympian. He was compared to a younger group of weightlifters, average age 23. The Master's lifter and the young lifters did identical workouts-and showed similar lactic acid levels during the exercise. The older man showed lower early-morning testosterone levels, which peak in the early morning, but his levels increased comparable to the younger men during exercise. Acute responses of cortisol, a catabolic stress hormone, and cortisol/testosterone ratios were also similar.

Even so, the older man's peak growth hormone release was far smaller than that of the younger lifters. The scientists concluded that resting and exercise-induced endocrine physiology is partially modified by aging, despite long-term competitive weightlifting training.

Lower Abdominals: Can You Train Them?

Most bodybuilders divide their abdominal training into upper, lower and occasionally side areas. Some trainers believe, however, that it's a waste of time (pardon the pun) to do specific exercises for the lower section of the abs. The area is mostly facia, or connective tissue, they say, and doing direct exercises offers few apparent benefits.Other trainees who are more familiar with the functional anatomy of the lower abdominals do understand the importance of direct exercise. There aren't that many choices. Most exercises thought to target the lower abs actually concentrate on the deep-lying hip flexor muscles, which aren't superficial but are nonetheless powerful and influential in many conventional abdominal exercises. For example, the classic full situp with feet braced almost totally involves the hip flexors when you raise your torso beyond the crunch, or contracted ab, position. The same holds true for full leg raises, hanging kneeups and seated knee-to-chest movements. Any abdominal exercise in which you hook your feet under something as a brace likewise diverts the work from abs to hip flexors.

This is a problem not just because you're no longer training your target muscles, the abdominals, but also because excessive hip flexor involvement pulls on the lower back, setting you up for future injuries. Most enlightened bodybuilders are aware of these abdominal exercise limitations and focus on partial movements, such as crunch situps, which do focus effectively on abs while avoiding hip flexor involvement.

So how can you isolate the difficult-to-train lower portion of your abdominals? Perhaps the best exercise is the reverse crunch. This involves lying on your back, then raising your bent legs toward your head, The resulting hip rotation effectively isolates the lower abdominals. It feels awkward at first, particularly if you're weak in the area. Recently, University of Hawaii researchers put aside their surfboards long enough to test the notion that you can, indeed, effectively train and isolate the lower abs. They had 17 athletes, including nine with previous lower-ah training and eight untrained subjects, do seven different abdominal exercises with surface electrodes attached to their abs to detect electrical activity.

The results showed greater electrical activity for both upper and lower abs in both groups during crunch situps and reverse crunches when performed on a 20 degree slant board. Reverse crunches, performed both flat and on a 20 degree angle, were the most effective lowerab exercises for the trained group, while the untrained group got the best lower-ab isolation while lying on their backs with their legs extended.

The researchers concluded that you can effectively train and isolate your lower abdominals, which strengthens the lumbar vertebral column, the lower back.