The Kinesiology Behind the Row - Understanding Back Muscle Training

There is Strong Science behind every Successful Workout

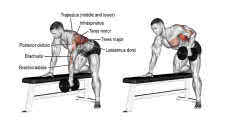

Rowing consists predominantly of motion at the glenohumeral joint of the shoulder; the scapulae, or shoulder blades; and

the elbow joints. Your shoulder moves from a forward, flexed position to an extended position behind your body. Your

shoulder blades go from a protracted (forward) position at the start of the movement to a retracted position as you

squeeze your shoulder blades together at the end. As a consequence of contracting your back muscles to achieve this full

range of motion, your elbows move from a fully outstretched, extended position to a flexed, bent position. Your torso,

hips, knees and other joint structures basically remain fixed. The muscles involved in maintaining their respective

positions contract isometrically to produce stability.

The major muscles involved in the movement of the active joints typically include your latissimus dorsi, teres major,

posterior deltoid, infraspinatus, teres minor, triceps brachii (long head) and pectoralis major (sternal head) during

shoulder extension; middle and lower traps, and rhomboids major and minor during scapular retraction; and biceps brachii,

brachialis, brachioradialis and pronator teres during elbow flexion.

Keep in mind that other motions at the shoulder joint occurring during the performance of the row can increase or decrease

the involvement of the aforementioned muscles, or recruit other muscles not typically used as prime movers in a row. For

example, if you stand more upright than normal during a bent-over row, your shoulder blades will shrug and rotate upward,

which involves the upper traps, levator scapulae and serratus anterior. In turn, this will minimize the amount of scapular

retraction and shoulder extension that normally occurs.